Will my Substack following grow exponentially?

Or is that an unattainable goal?

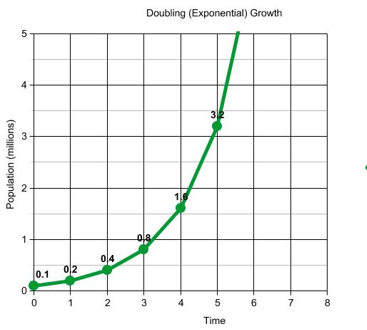

When Sophia Efthimiatou from Substack predicted my subscribers would increase exponentially, I began seeing a starry future. Exponential! The Holy Grail of growth! The reason bacterial populations double every few minutes—one bacterium divides into two, then each offspring divides into two, and so on. It’s the same doubling pattern (1,2,4,8,16…) that tracks how a single infected person might spread the flu. And now my following was going to behave similarly, spreading like the pandemic to colonize the world. Forget Typhoid Mary, make way for Substack Suri!

So I posted my first Substack. At 10:35 a.m. on Wednesday, Nov 26. I sent links on all my (rather meagerly subscribed) social media accounts and sat back to watch the coming exponential explosion.

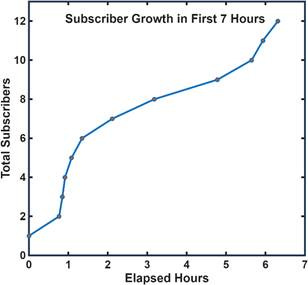

Sure enough, at 11:21 a.m., Substack sent me an email saying my following had doubled – from 1 (myself) to 2. (Thank you Nick Li , my stand-up comedy buddy and from now on, eternal blood brother.) At 11:26, my artist friend Mark Woods signed up, followed at 11:30 by Sandy from my Improv class. I had not only doubled but redoubled! Seven hours in, I graphed all the info from the emails so that I could sit back and savor my subscriber growth.

Alas, it was by no means exponential. Which was to be expected, since none of my initial subscribers had pulled in any additional subscribers of their own yet. Given that it was Thanksgiving eve (not the smartest timing on my part), perhaps this secondary cache would come only after the festival, once people had a chance to repost my debut.

It didn’t happen. Oh, there were promising junctures, when it seemed like I was finally going to take off. But the graph always flattened out, since I just hadn’t provided Substack with enough of a starting population. I tried to feed the beast, digging up more emails, asking family and friends, even threatening my followers on Facebook that I’d be shutting down my account so they’d better switch to Substack. But people are fickle—not dependable like bacteria. My Facebook prod elicited a collective yawn.

I asked Sophia if she’d really meant exponential growth. She said that’s what the model predicted. “This is a model where for as long as you do it your list will grow…more and more people will discover you and sign up.” Indeed, it did sound like she was articulating the standard mathematical assumption behind exponential growth: the more subscribers you have, the more the chances of propagation, so the faster (proportionately) your numbers will grow.

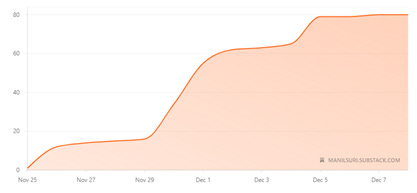

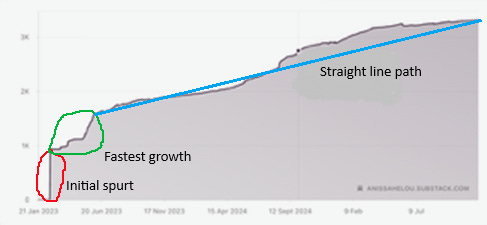

Clearly, it wasn’t going to show in my transient phase, but had long-term Substackers actually seen exponential growth? I tapped my friend Anissa Helou, chef and cookbook author extraordinaire, who has such elevated expertise in Lebanese (and other) cooking that I call her Goddess. She was kind enough to share her all-time Substack subscriber data.

The first thing that struck me was the 1K spurt at the beginning. Anissa had entered the email addresses from a mailing list of folks she had been regularly sending posts to. Something I’d never done, which meant I was list-less. Clearly, I faced a long slog ahead.

I also noticed the graph grew fastest after this spurt. But the rest of the curve could pretty much be averaged by a straight-line path. I saw no indication of it settling into an exponential pattern.

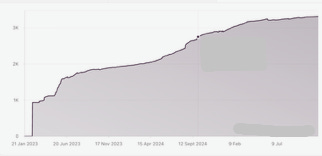

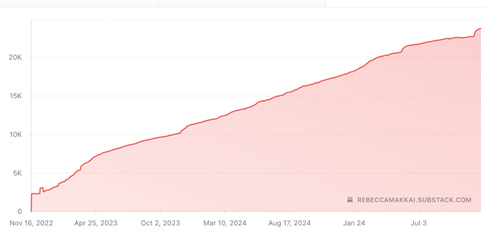

Next, I approached the most heavily subscribed Substacker I know: Rebecca Makkai, with whom I share a literary agent. Rebecca’s novel, The Great Believers, was named one of the top books of the 21st century by the New York Times—need I say more? She generously shared her data as well.

Yes, dear reader, a worrisome (for me) initial burst kicked things off here too. And then, just like in Anissa’s case, came the period of fastest growth (until about Apr 25, 2023). Followed by a curve that once again looked pretty close to linear. Not exponential.

What this suggests to me is that with Substack accounts even as successful as Rebecca’s, one can expect long-term growth to be steady, robust, and linear—but probably not exponential. I suspect that’s because in the bacteria model, each offspring is guaranteed to subdivide, thus adding a whole family tree of new members to the population. But in Substack, new subscribers may not repost (“restack”) at all. Or, if they do, then these restacks may not generate enough new followers. In particular, not an entire family tree’s worth, as the exponential model assumes.

Of course, for all I know, both Anissa’s and Rebecca’s growth curves have just been waiting for my foolish pronouncement to go exponential, twin rockets zooming into the stratosphere to prove me wrong. Until that happens, though, or until someone can show me convincing data from actual Substackers, I’m going to regard such curves as urban myths, as unicorns. And be grateful if I can be assured of at least long-term linear growth.

Disclaimer: I’ve used “exponential” rather loosely in this post—please see my New York Times piece, Stop Saying ‘Exponential.’ Sincerely, a Math Nerd for the fine print on what qualifies. Also, one factor which can dampen exponential growth in bacteria is saturation—limited resources (e.g. food, space) can put an upper limit to how much the population can grow. Something similar might be contributing to the growth rates seen in Substack—perhaps a topic for a future piece. And another obvious topic: how is the rate at which you post related to the growth?

It seems like the growth has two time scales (like an initial boundary layer, and a slower outer layer; sorry, too technical; the old math guy coming back to me). The most interesting graph is the one with multiple plateaus, indicating interesting dynamics going on.

You should have explained this more mathematically! "Exponential" may be a matter of measure theory. If you consider that all accounts start with one subscriber, than after a time period of n, the discrete measure of exponential must necessarily mean that a discrete interval can be found justifying exponential growth. For instance, if the number of subscribers is eventually 10, than a discrete exponential interval can be to fit the exponential function from 1 to 10. (And the worst case is 2, which is also exponential.)

The definition, however, that you're using is the mathematical definition: a derivative at any point of any exponential function is an exponential function. This fits the data. But it isn't necessarily what your friend meant!